Building a Welding Program from the Ground Up

Former Welding Instructor Leland Vetter Reflects on the Program’s Humble Beginnings

Leland Vetter stands with Sandy Rueb infront of the sculpture he built and Rueb the designed. The sculpure stands at the entrance of the Fine Arts building on Eastern Wyoming College’s Torrington Campus.

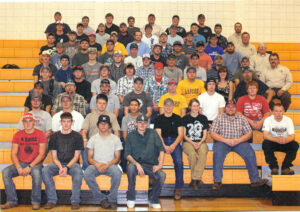

The 2013-2014 welding class at Eastern Wyoming College.

By Olivia Wieseler Thomas

EWC Communications

After a long day in the oil fields of North Dakota, 21-year-old Leland Vetter got a phone call from a Wyoming man named Guido Smith asking him if he’d be interested in starting a welding program at Eastern Wyoming College (EWC).

School had never been for Vetter, so teaching was the last career he would have considered for himself. But apparently his instructors at North Dakota State School of Science saw potential in him. When they ran into Smith at an ethanol conference in Iowa, Smith told them he wanted to build a welding program at EWC. They said, “Hire this kid,” referring to Vetter.

“We (Smith and Vetter) talked on the phone a few times, and then I went on spring break to California with some friends … and then I stopped in to see Guido,” Vetter said. “He would call it an interview but it wasn’t. We had a cup of coffee, and we walked around. … Then he offered me the job.”

Vetter took the job, telling his then-girlfriend (now wife) he’d stick around for a year and then move back home.

They ended up making Torrington their home for 34 years.

During that entire time, Vetter not only stayed at EWC as a welding instructor, but he also helped build the program into one of the best in the state, if not the country.

“We weren’t an easy training program,” he said. “I worked them hard. Those were not the easiest classes on campus, but the students knew we were serious about welding.”

Of course, there was a learning curve at the beginning. Vetter had to build a program from scratch as a recent graduate himself. Luckily, he had a little help from one of his instructors at North Dakota College, who was retiring that year.

“He gave me like four boxes of files of every test and everything that he had, and he gave it all to me,” he said. “So, when I got hired there, Guido got me an office, gave me a legal pad and a pen, and said, ‘put together a program.’”

Vetter quickly decided what he wanted his program to look like. It would be simple, but not easy. No homework, tests returned the next day — but high expectations.

“I wouldn’t accept anything from students that wasn’t absolutely good, meeting industry standards,” he said. “That had to be there. I just wanted them to be real good. And the students really responded to it.”

It wasn’t just the students being pushed to do their best, however. With no teaching background, Vetter found that the students actually helped him as an instructor.

“I learned so much from them (the students),” he said. “Eastern Wyoming College taught me how to teach. And when you teach a lot of students, you never stay the same. You either get better or you get worse; you don’t stay the same. So, I tried to get better every day.”

Thanks to this mutual understanding between Vetter and his students to always do their best work, the program began to flourish.

Soon, word got out about this welding program in eastern Wyoming, and students from all over the country came to get a serious welding education. The program grew from eight students the first year to around 100 students in 2014 when Vetter retired.

The program didn’t just expand in number of students either. Vetter went from teaching in a high school FFA classroom to envisioning EWC’s current $24 million tech complex and designing the welding labs within it. He taught traditional and non-traditional students during the day and in the evenings. He added a machine tool program, trained inmates using a mobile welding facility, and even conducted industrial safety trainings for companies as far away as Montana during the summer.

While his decision to retire in 2014 was a tough one, he felt he couldn’t have gone out any better.

“I was on top of the hill,” he said. “It was just a grand time.”

Vetter retired to move his family back to North Dakota so they could help take care of his aging parents. Still, his contributions to the college have not been forgotten by the faculty, staff and community, which is why he was awarded the 2024 Albert C. Conger Service Award.

Being the humble person he is, Vetter was in shock at first, and then attributed his contributions to the people he worked with.

“I was taken aback when I got the phone call … because I’m sure there are hundreds that have done more than I have,” he said. “I often wonder if I could repeat it — do it again somewhere — and I know that I couldn’t because you need to be surrounded by the right people.

“Everything really fell into place for me. I really was at the right place at the right time with the right people.”